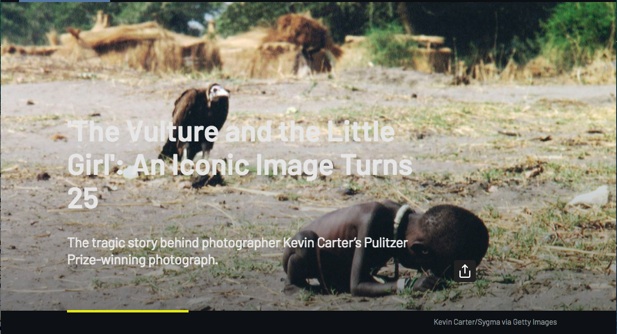

'The Vulture and the Little Girl': An Iconic Image Turns 25

The tragic story behind photographer Kevin Carter’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph.

Kevin Carter/Sygma via Getty Images

Photographs by Kevin Carter

Words by Amy Wilkinson

(A note to our readers: This story contains photographs that are violent and disturbing.)

"Why didn’t he help her?"

"How could he just leave her there?"

"What became of her?"

The haunting image of an emaciated Sudanese child — collapsed in a heap on the way to a United Nations feeding center, vulture perched ominously nearby — ignited worldwide sympathy and outrage when it was published in the March 26, 1993 issue of the New York Times. The photo, known alternately as "The Vulture and the Little Girl" and "Struggling Girl," would become emblematic of Africa's plight in the 1990s — and earn a Pulitzer Prize for its photographer, 32-year-old South African Kevin Carter.

Yet, the shot, powerful in its simplicity, raised tough ethical questions about the role of the photojournalist — to document or to intervene? Carter said he shooed the bird away after getting his picture, but some editorial writers argued that wasn’t enough. "The man adjusting his lens to take just the right frame of her suffering might just as well be a predator, another vulture on the scene," chided a 1994 article in Florida’s St. Petersburg Times.

Kevin Carter/Sygma via Getty Images

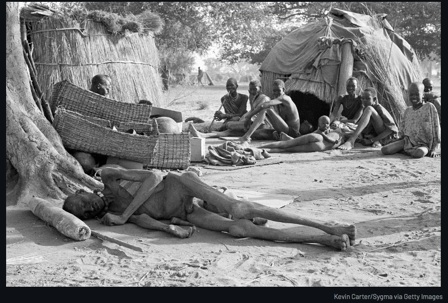

Sudanese famine victims in a feeding center

Twenty-five years later, the photo's complicated legacy endures. "Struggling Girl" is considered a seminal work of modern photojournalism — uttered in the same breath as Nick Ut's image of a naked Vietnamese girl fleeing napalm, Dorothea Lange's "Migrant Mother," and Eddie Adams' photo of a Vietnamese man being executed in the street. And, like many of those images, it still polarizes.

"Struggling Girl" also proved to be something of a tragic bellwether for the man who captured it. Just four months after accepting his Pulitzer at New York's Columbia University, Carter died by suicide in South Africa. He was 33 years old.

Kevin Carter/Sygma via Getty Images

In this photo from 1994, a policeman stands at the scene of shacks set alight in South Africa.

Born September 13, 1960 in Johannesburg, Carter came of age during the height of Apartheid, troubled by his parents' indifference to the struggle. After graduating from a Catholic boarding school in 1976, Carter started and then abandoned a number of pursuits — pharmacy school, the Army, disc jockeying — eventually landing a job at a camera shop. Photography was a natural extension. He cut his teeth as a sports photographer at the Johannesburg Sunday Express before moving to the Johannesburg Star with the intention of exposing Apartheid's brutality.

Kevin Carter/Sygma via Getty Images

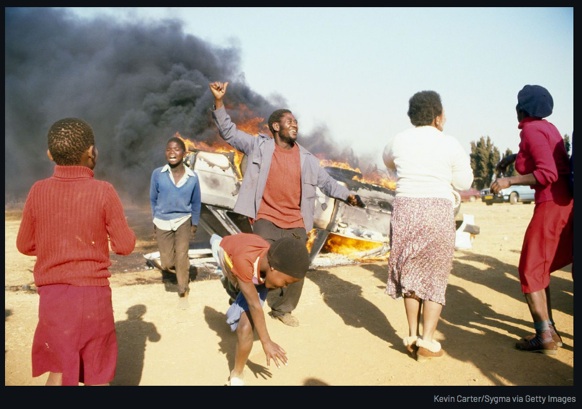

In this undated photo, a riot breaks out in Duduza township during a funeral.

At the time, a white photographer working the beat was something of a rarity — capturing the bloody violence had largely been the province of black photographers. As tensions in the area grew, Carter aligned himself with three other young photojournalists who would work and travel together for safety. They were Ken Oosterbroek, Greg Marinovich, and Joao Silva, later known collectively as "The Bang-Bang Club," owing to their ability to always be in the middle of the conflict.

Kevin Carter/Sygma via Getty Images

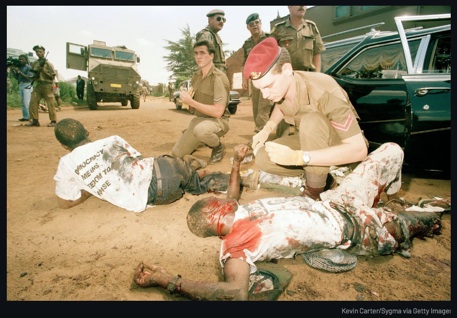

South African Defence Force medics treat victims of a grenade attack in February 1994.

In 1990, the same year Carter started the photo department at the Daily Mail, civil war broke out between Nelson Mandela's African National Congress (ANC) and the Zulu-supported Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP). And even though the Bang-Bang Club moved as a pack, danger — and the real possibility of death — was never too far away.

Kevin Carter/Sygma via Getty Images

Murder of a woman suspected of collaboration with the police.

The men bore witness to grisly beatings, stabbings, shootings, and necklacings (in which a petrol-filled tire is forced around a victim's neck and set on fire). The horrific conditions made their work perilous, yet powerful. Marinovich would be the first Bang-Bang Club member to receive wide acclaim for the brutal images he shot: His photo series of a Zulu supporter being stabbed and set on fire by ANC supporters won the Pulitzer Prize in 1991.

Kevin Carter/Sygma via Getty Images

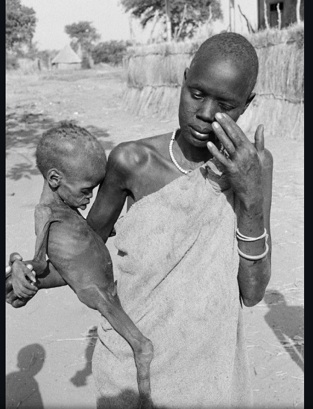

This photo of a starving Sudanese child earned Carter a Pulitzer in 1994.

By 1993, burnt out on the South African conflict, Carter sought respite (or, at the very least, a change of scenery) in southern Sudan. With borrowed funds, he made the trip alongside Silva, hoping to document the famine and civil war largely ignored by the media. Immediately after landing in the village of Ayod, Carter began snapping images of famine victims, and it was then that he heard the faint whimperings of a Sudanese child. He later told reporters that after getting his shot and shooing the bird away, he sat under a tree, smoked a cigarette, and cried.

Another scene from the feeding center

Interestingly, the photo itself wasn’t the story — at least not at first. Around that same time, New York Times editors were in search of an image to illustrate an article about the Sudan and were tipped off to Carter's photo by Marinovich.

"Struggling Girl" inspired such an influx of reader letters, that the Times issued a special editor's note a few days later: "A picture last Friday with an article about the Sudan showed a little Sudanese girl who had collapsed from hunger on the trail to a feeding center in Ayod. A vulture lurked behind her," read the note. "Many readers have asked about the fate of the girl. The photographer reports that she recovered enough to resume her trek after the vulture was chased away. It is not known whether she reached the center."

Kevin Carter/Sygma via Getty Images

A famine victim

Carter's image would run in newspapers around the globe. And with his career and confidence growing, he quit the Daily Mail to go freelance. But the high wouldn’t last.

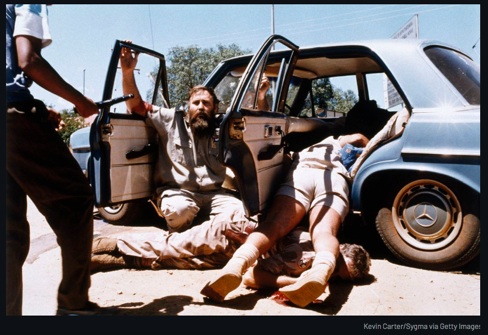

Kevin Carter/Sygma via Getty Images

A shootout between Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging and the Bophuthatswana Defence Force

Carter returned to war-torn South Africa, and about a year later would take another indelible image — one he considered a disappointment. While shooting the scene of three Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) members being shot in Bophuthatswana, Carter's camera ran out of film. By the time he reloaded, he was only able to record the aftermath (above). Still, his photo became frontpage news, even if he couldn’t shrug off the feeling of failure.

"I knew I had missed this f------ shot," he said. "I drank a bottle of bourbon that night."

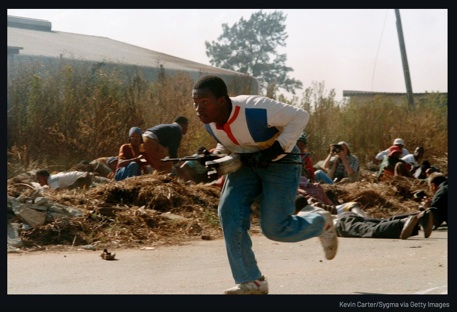

Kevin Carter/Sygma via Getty Images

Fighting between the ANC and IFP in Thokoza township

But a much deeper cut would come the following month. On April 18, the Bang-Bang Club headed to Thokoza township, just outside Johannesburg, to photograph a gun battle. Carter returned to the city around noon, citing the inhospitable lighting conditions of the midday sun; while driving back, he heard over the radio that his friend Oosterbroek had been shot and killed. By all accounts, Carter was gutted by the loss. Yet he returned to work the following day, capturing images (like the ones above and below) in the same region.

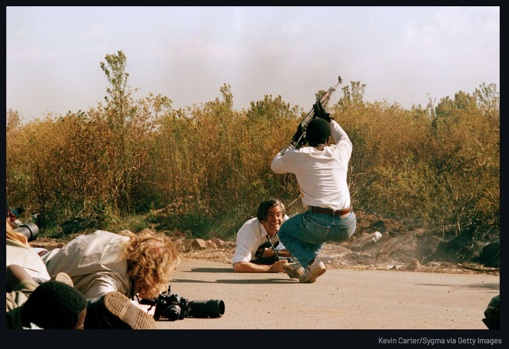

Kevin Carter/Sygma via Getty Images

Photographer James Nachtwey, at center, hits the ground during the street battle in Thokoza.

In May, Carter traveled to New York to accept his Pulitzer. Just two months later, on July 27, 1994, Carter, back in South Africa, parked his pickup near a favorite childhood play spot, connected a garden hose to the exhaust pipe, and snaked it through the passenger-side window. The cause of death was ruled carbon monoxide poisoning. In his suicide note, Carter wrote: "I'm really, really sorry. The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist. I have gone to join Ken, if I am that lucky."

Carter left behind a six-year-old daughter from an earlier relationship and a collection of hundreds of powerful, provocative images, laying bare conflicts and casualties too often ignored.

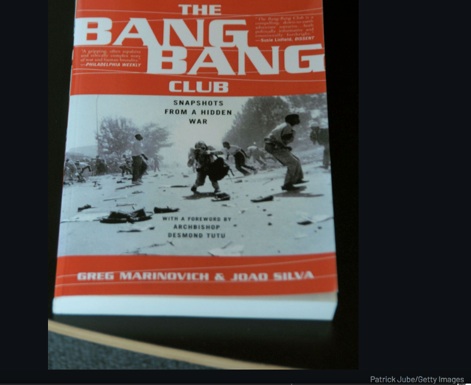

Patrick Jube/Getty Images

A photo of Carter at work covers the Bang-Bang Club memoir.

In 2000, the two surviving Bang-Bang Club members, Marinovich and Silva, published a memoir, "The Bang-Bang Club: Snapshots From A Hidden War," detailing their time in South Africa. The book was adapted into a film of the same name in 2011.

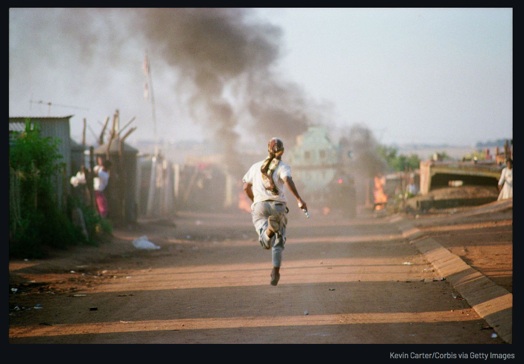

Kevin Carter/Corbis via Getty Images

Another scene from the riot in Duduza township

As part of the press surrounding the film’s release, Marinovich reflected on his friend Carter.

"Life with Kevin was never dull," he said. "He was warm and generous and fun and crazy. And also aggravating and annoying and an addict. At the heart of it he was a wonderful person."

A Footnote

In 2011, a reporter from the Spanish newspaper El Mundo traveled to Sudan to investigate the whereabouts of the struggling girl Carter so famously photographed. As it turned out, the paper reported, she wasn’t a girl at all. The child was a boy named Kong Nyong, who according to his father, survived the famine but died in 2007 of "fevers."